I wonder whether Orgreave House feels uncertain…. and a little wistful…. about its identity? After all, if it wasn’t for its gracious neighbour, the Queen Anne mansion of Orgreave Hall, it would be the largest and most imposing dwelling in our hamlet.

And its architectural personality is full of contradictions.

It turns its Sunday face to the south. Bay windows bulge from its two principal reception rooms, scanning a large, sweeping lawn, that is adorned by a majestic cedar tree. The formal entrance drive – protected by a surprisingly substantial cattle grid – curves its way through mature rhododendrons, that welcome visitors with large gaudy blooms in the springtime.

But if you should make the muddy trudge to the rear – tradesman’s – entrance, where a gate leads into a generous courtyard bordered with outbuildings, the house squints at you as you pass the utilitarian windows of its north facing service rooms. On this side, the building abuts immediately onto the now blind ended track, that long ago and for many centuries gave access past the site of the Hall to Alrewas and beyond. No longer troubled by the passages of cart, pack horse and pedlar, instead it endures its proximity to what is a rutted shunting area for Hall Farm’s big, busy, blundering, pea-green tractors.

But if you should make the muddy trudge to the rear – tradesman’s – entrance, where a gate leads into a generous courtyard bordered with outbuildings, the house squints at you as you pass the utilitarian windows of its north facing service rooms. On this side, the building abuts immediately onto the now blind ended track, that long ago and for many centuries gave access past the site of the Hall to Alrewas and beyond. No longer troubled by the passages of cart, pack horse and pedlar, instead it endures its proximity to what is a rutted shunting area for Hall Farm’s big, busy, blundering, pea-green tractors.

And the north-eastern corner of the house terminates most oddly in a single, foursquare crenellated tower.

The Orgreave House of two hundred and fifty years ago I imagine as a neat and almost symmetrical Georgian building, that still secretly forms the south-western core of the present house. Much later “improvements”, including the tower, the parapets atop the porch and bays, and the asymmetrical extension to the east, suggest inspiration drawn dilutely from the Gothic Revival style.

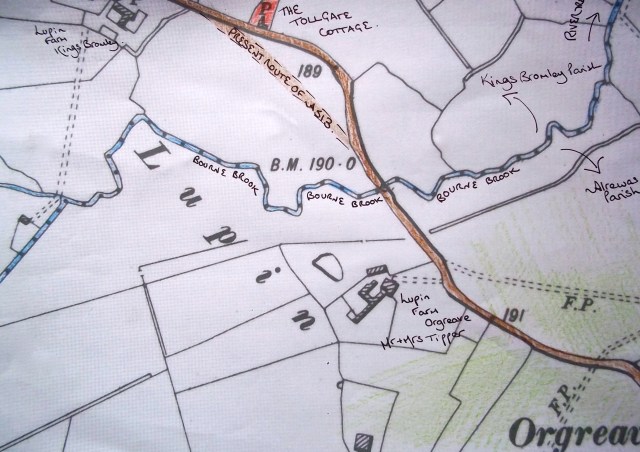

Annotated map of the Orgreave and Alrewas estate, from circa 1760, the original of which is kept at Stafford record office. Since then, a tennis court (shaded blue) has been laid against the site of a now extinct cottage, its grounds subsumed into Orgreave House’s extended gardens. Indicated in red, a bulky extension has created an East Wing, and the space between the building and the lane has been filled in, partly by the tower.

A map held at Stafford Record Office helps to put this house into context in mid 18th century “Orgrave” – as the cartographer spelled it – probably during a survey conducted in connection with the purchase of the Alrewas and Orgreave Estates by Admiral Lord Anson from the Turton family.

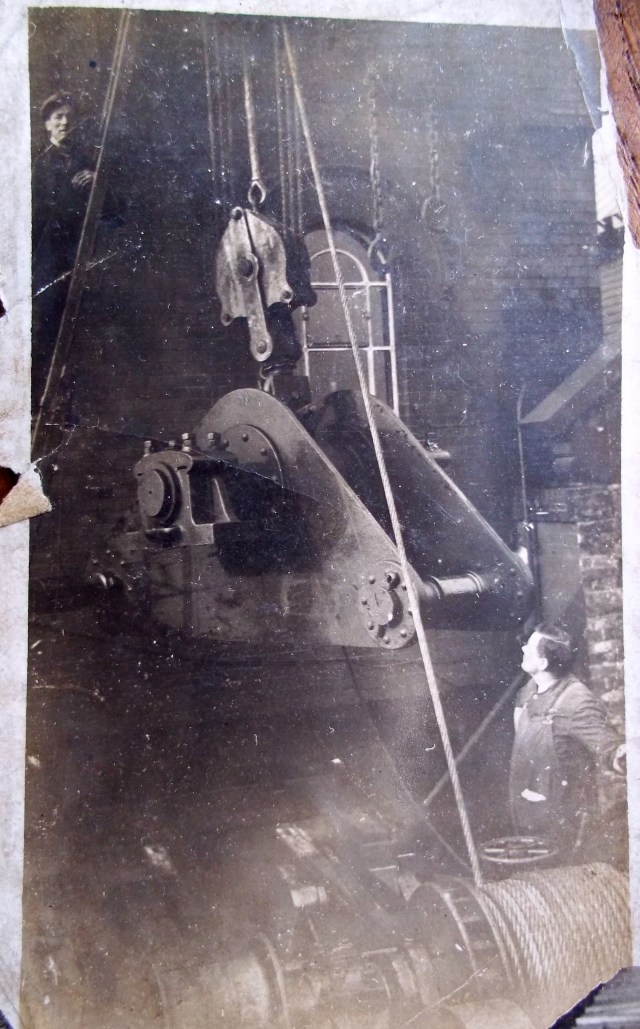

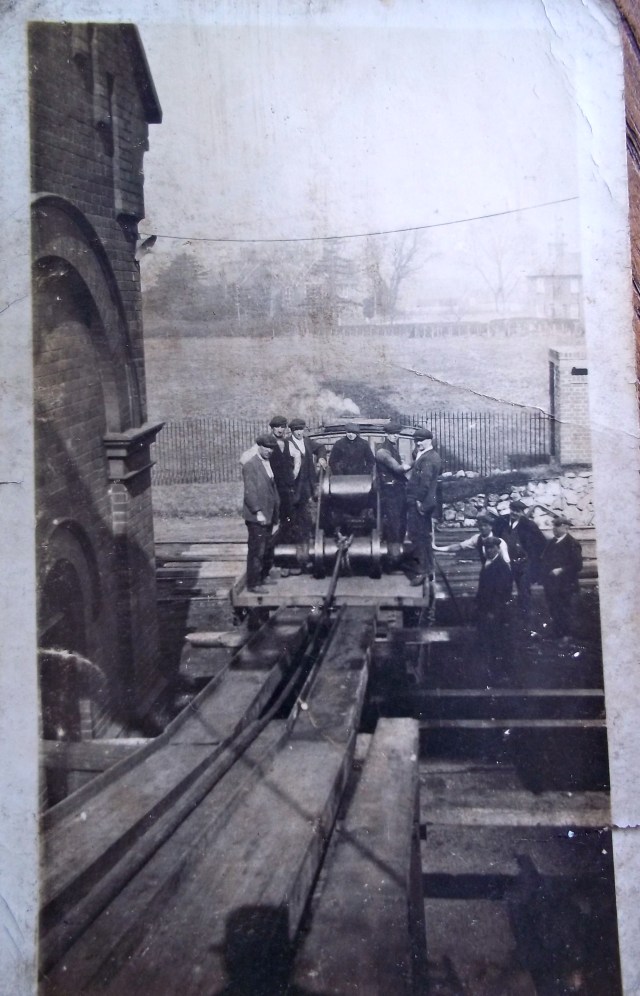

At the end of the 19th century, alterations to the house, and development of the outbuildings to provide copious stabling were undertaken by Mr. Henry Edward Audley Charles, with assistance from Walsall architects H. E. Lavender. The Lichfield Mercury of 29th November 1901 speaks of veterinarian Mr Charles’ “equine veterinary hospital” at Orgreave House, although he had been at pains to publicise, via his own advertisement in the newspaper that year, that his “shoeing forge” had been transferred from here to Frog Lane, Lichfield.

OS 1881 – Prior to the extension of Orgreave House. http://www.oldmapsonline.org

OS 1901 – Following the extension of Orgreave House. http://www.oldmapsonline.org

Mr. Henry Edward Audley Charles was a scion of the affluent Charles Family of Pelsall Hall, but his family had deep roots in Orgreave: His grandmother, Catherine, who married Thomas Charles at All Saints Church, Kings Bromley on Christmas eve in 1816, had been born in Orgreave. Her father, Henry Smith, is described – in his will of 1817 – as a Yeoman, in possession of the copyhold and freehold of various local tracts of land.

Catherine and Thomas’s second son, Abraham Charles, took up some of his matrilineal inheritance at Orgreave, where he settled with his wife, Hephzibah. Their son, Henry Edward Audley Charles was born at Orgreave in January 1871, but, sadly, the beautifully named Hepzibah died only weeks later.

Happier times, perhaps, are captured by the enumerator of the 1901 census as he visited Orgreave House. Now 30, Henry, the successful veterinarian, and his wife Kate, live here with their eight year old daughter Muriel and her three younger brothers, Edmond, John, and Hugh. A governess and nurse are on hand to take care of the children, whilst a groom and two maids attend to other domestic duties. Intriguingly, the whole family shortly up-sticks and emigrate to Canada, where Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton, was pursuing a vigorous policy of inviting suitable new citizens to his country. Farmers were preferred, but opportunities must have been manifold for an expert equestrian vet, in that horse powered age.

Orgreave House is thus available to let. What sort of tenant would be soothed by the familiar toy-fort tones of its nether reaches, and appreciate the ample accommodation available for their grooms and horses? Who better than senior army officers, from the local Whittington Barracks?

“ORGREAVE HOUSE, Near LICHFIELD: Telegrams – Alrewas. Railway Stations – ALREWAS – 1 1/2 miles. CROXALL – 3 miles. LICHFIELD (T.V.) – 5 miles

Wintertons auctioneers held a sale of some of the effects that are no longer required by Captain Occleston and his wife in the spring of 1909, as they prepared for their posting abroad. The keys to Orgreave House were duly handed over to Brigadier General George Frederick Gorringe, C.M.G., D.S.O, appointed in April 1909 as Commander of the whole 18th Infantry Brigade at Whittington. What with the Sports Club, the officers’ Golf Club, the Barracks’ own Beagle Pack and the meets of the South Staffs or the Meynell Hunt who drew the coverts within easy reach of Orgreave, the Brigadier General was unable to make it to the Grand National in 1911. A piece of ephemera that has fluttered its way to me on the etherial breeze from eBay lets me peep at him making his courteous apologies to “May” from his desk at Orgreave:

Orgreave House, Near Lichfield

21 March 1911

My dear May

I am so very sorry but I shall not be able to accompany you to the National – I saw Herbert Hamilton & he is going from Stafford with Sir Bruce….but Thompson is going and Percival from here & possibly others who you know. So I do hope you will come here all the same, or my slump of luck will be indeed be heavy so au revoir on Thursday.

Yours as ever

G.Gorringe

At the races in 1911. http://castaroundlesmodes.tumblr.com/post/63273035681/mode-aux-courses-1911-1914

The old charmer. Did May manage to rendez-vous with the party at Orgreave that Thursday, I wonder, and travel with Percival to Aintree? Did she arrive unchaperoned, with her huge hats and her furbelowed skirts to what was an almost exclusively masculine menage at Orgreave House? Just a week or so later, on Sunday April 2nd, 1911, in Gorringe’s distinctive, confident handwriting, he makes a list of his household for that decade’s census, noting that the house boasts a plentiful 20 rooms. The Brigadier General, his brother, Leonard, and the horses, are being cared for by a staff of eight young men – a butler, footman, orderly, kitchen boy, gardener, and three grooms. The gardener’s new wife, Sarah Powell, Gorringe’s cook, is the only woman in the place. Contrast this manly crew with the staff controlled by the butler in the employ of William Edward Harrison at nearby Orgreave Hall – it is its mirror opposite. There, Mr.Bird finds himself in charge eight female staff – cook, lady’s maid, and a small flutteration of young maids and children’s nurses – this a much more typical profile, as female domestic staff are both more numerous and considerably cheaper than their male counterparts in 1911.

From the Imperial War Museum collection. General George Frederick Gorringe, C.M.G., D.S.O. 1871-1945

George Gorringe was a bachelor in his forties during his appointment at Whittington between 1909 and 1911. Over 20 years in the regular army had seen him actively – and effectively – involved in a remarkable six military campaigns. During the Mahdist War in the 1890s in Sudan, he brushed shoulders with both Winston Churchill, and the more famous Lance Corporal Jack Jones. When Corporal Jones’ mentor, Lord Kitchener, had secured the reconquest of the Sudan at the Battle of Omdurman, and overseen the first steps in rebuilding Khartoum ( a process in which Gorringe was said to be closely involved), Gorringe left Sudan for South Africa with Kitchener, as his temporary Aide-de-camp. During the Boer War, Gorringe cemented his reputation as an effective soldier, although his heirs have judged him harshly for his role in the execution of justice against civilians who he deemed to have been assisting the Afrikaner enemy. How strange life must have been for him, marooned here in Staffordshire, in temperate weather, with no apparent threat to his life, an active social life to conduct, and the prospect of semi-retirement in “staff” roles for the rest of his career.

Winston Churchill desperately sought out the conflict in Sudan of the late ’90s as the only live theatre of war in which he could test his mettle as soldier and as writer. His first publication “The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan” was the fruit of that. By the time the Great War was really underway in 1915, no British – or Colonial -man had to look far for the opportunity to fight. In Canada, Henry Edward Audley Charles joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps. An experienced officer like Gorringe was, of course, a most valuable asset to the army. With his endurance both of unfavourable climates and the difficulty of waging war where insect infested water was both too deep for tanks and too shallow for boats, he was given a command in Mesopotamia (present day Iraq). Himself a 21st century soldier with experience of fighting in Iraq, Paul Knight mentions Gorringe in his book “The British Army in Mesopotamia, 1914-1918.”

…….if ever a determined General was needed to force through a victory on the Euphrates, it was Gorringe. Russell Brandon, writing in 1969 considered him to be: “…..the ideal man for a relentless slog. A big man, highly coloured, deeply tanned, officious and utterly without tact. He reminded those less insensitive than himself of an enormous he-goat, and allowed nothing – not Turks, counter-attacks, casualties, swamps, Marsh Arabs, or deeply entrenched redoubts to stop him.”

He doesn’t sound like a fellow that May would have recognised.

Mother and I spent the following – then requisite – several days of complete rest both happily be-pillowed between the dark polished oak headboard and footboard of my parents’ bed at Bosty Lane. Aunty Rene kindly double-bussed it from Stonnall to make light of the housework, and a community midwife attended to us. Mrs Gombridge was that right-thinking professional who seems to have esteemed dogs at least as highly as she did babies. Two large mongrels accompanied her on her rounds, panting and wagging their tails in her little car as she made her calls on new mothers, and her dark uniform was liberally coated with their hair. She put paid to any misgivings my mother had about big dogs and new babies and briskly insisted that Simon should be introduced to his new human immediately. His kind brown eyes watched protectively over me for the next several years. With angelic patience, he suffered my little arms to probe deep into his soft liver-and-pink mouth to retrieve an important piece of Lego that he might have purloined from my play.

Mother and I spent the following – then requisite – several days of complete rest both happily be-pillowed between the dark polished oak headboard and footboard of my parents’ bed at Bosty Lane. Aunty Rene kindly double-bussed it from Stonnall to make light of the housework, and a community midwife attended to us. Mrs Gombridge was that right-thinking professional who seems to have esteemed dogs at least as highly as she did babies. Two large mongrels accompanied her on her rounds, panting and wagging their tails in her little car as she made her calls on new mothers, and her dark uniform was liberally coated with their hair. She put paid to any misgivings my mother had about big dogs and new babies and briskly insisted that Simon should be introduced to his new human immediately. His kind brown eyes watched protectively over me for the next several years. With angelic patience, he suffered my little arms to probe deep into his soft liver-and-pink mouth to retrieve an important piece of Lego that he might have purloined from my play.