In the early 1950’s, in the rural hamlets of Footherley and Lynn in South-East Staffordshire, where my father’s family lived, darkness fell almost as thickly in the evening as it had done before wartime. In the tiny rooms of Keepers Cottage, Josephine-Ann read her school-books in the pale pool of light bestowed by a gently hissing paraffin lamp. Neither did our cousin Rosalind and her parents, over the fields at The Owletts Hall Farm, enjoy a supply of mains electricity.

Before hostilities got underway in ’39, the army had arrived, and they had been the bearers of light.

Bouncing up the tree-lined drive to the farmhouse in small lorries, men set up a searchlight in the orchard, and, about 300 yards away in the field, sited a diesel generator to power it. The purpose of this installation was to point an accusing finger of light into the sky at the German bombers sneaking towards Birmingham and the Black Country. Mobile anti-aircraft guns would thus be given a helping hand to pick them off before they did too much damage. One night, a second enemy aeroplane, following, unnoticed, aimed a bomb at the source of the beam. The generator and searchlight were untouched, despite the deafening explosion. The cable had been cut – the searchlight was out of action for a few hours – but there was no loss of life, despite the doom-laden quick-fire gossip already crackling round Shenstone the following morning. One lady swooned with shock on the station platform, seeing what she assumed to be the spectre of my Aunt Mary hoving into sight with a wicker basket over her arm, to catch the mid-morning train into Lichfield to shop for provisions. Even in 2012, the late Joe Bower of New Barns Farm, interviewed by the Lynn and Stonnall Conservation Society, told them that he believed there had been two fatalities in the orchard that night. This was an exaggeration, but, sadly, a new, young recruit from Edgbaston, who had been manning the equipment when the bomb dropped, lost an arm in the incident.

The “Owlet Hall” had stood in its level, lightly wooded setting long enough to have heard the departing rumble of the English Civil War when that trouble had crawled back and forth through Lichfield City and its surrounding villages in the 17th century. Its new battle scar, a modest crater by 20th century standards, was first a dish, and then a saucer, and then all-too-soon discernible no more, levelled with general detritus from the farm.

The Coopers, Rosalind’s grandparents, Charles and Charlotte, her father, Alfred, and her many aunts and uncles, had come to Lynn from their previous tenancy, Warren Farm, Drakelow. They were part of an influx of farming families who arrived in the Shenstone area during the inter-war period to take advantage of its fertile soil and level pasture. The Fodens came because they found their stamping ground at Queslett becoming part of the northern conurbation of Birmingham. And my dad was told by Old Sam Ikin tales of the memorable wagon train of workforce and effects taking to the road from Wem, when his people had moved east to Druids Heath.

The Coopers had arrived to take on both The Owletts and The Diary Farm on Lynn Lane, so there was adequate local accommodation for the whole family when The Owletts was requisitioned at the outbreak of war to provide accommodation for the military.

Between jobs “in service” in the early 30’s, my Aunt Mary had glanced admiringly, from the back of a rattletrap lorry, at the quaint, late Victorian, single storey lodge at the end of The Owletts drive, as, wedged between the other women, she had headed off for hard days of potato picking. In 1937, having married her neighbour Alfred Cooper, it became her first marital home, where she was to welcome in two waves of evacuee children, and to cower stoically from falling plaster on the night the bomb dropped.

The army personnel vacated the Owletts for their camp, leaving behind some interesting pencil drawings on the plasterwork on the landing, and some rudimentary electrical wiring to make use of the excess output of the military generator. Mary and Alf moved in to the farmhouse, whilst “Granny and Grandad” Cooper, now in their mid-sixties, retired to live in The Lodge. Rosalind was born in 1943.

At Keepers Cottage, latrine facilities remained an old fashioned two-holer earth closet in a brick privy in the garden – right up to, I remember well, Mary’s brother, my Uncle Bill – the last surviving tenant – died, in the 1980s. However, at The Owletts there were water closets and a bathroom – luxury! – but still no mains electricity as the 1950’s began. The huge pylons that now dominate this view had not yet strode titanically across the landscape to stand in a monumental line between Walsall and, co-incidentally, Drakelow.

Young Rosalind Cooper, in her Borrowcop School Uniform, is able to complete her homework, courtesy of the Lucas Free-light system.

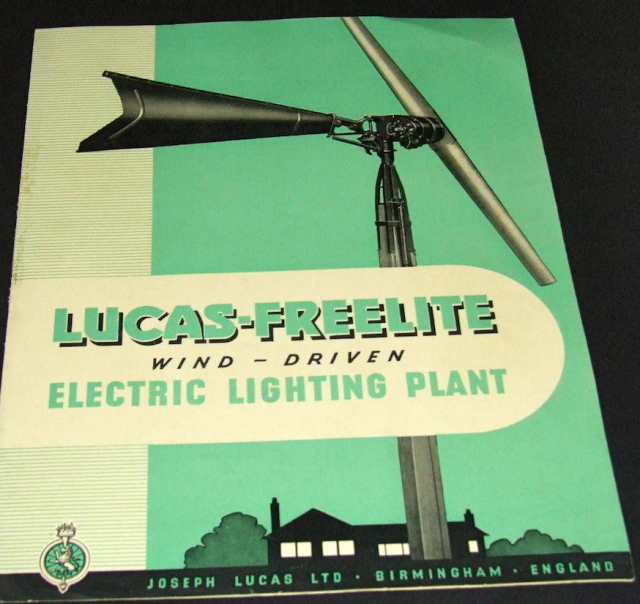

Someone had a bright idea. A Lucas Free-light wind turbine could be trialled at The Owletts, and in return for the stunning convenience of free light and free ironing – and even television -at the flick of a switch (adequate recent wind permitting) – Lucas could arrange for some publicity shots of the Cooper family enjoying the conveniences that many townies had long taken for granted.

The electric iron was often the first household device to be purchased. It plugged into the light socket. Here my Aunt Mary feigns delight in smoothing her daughter’s school dress.

Cousin Rosalind remembers the monthly manifestations of the engineers, Mr. Brentano and Mr. Greatrex, to monitor the equipment. Their little shed, housing dials – one clearly labelled “amperes per hour” – was a warm and woody secret place for a young girl to explore. A table supported massive batteries which stored the power they drew upon in the farmhouse.

Two small pylons were erected: one was sited in the orchard, the other in the field next to it, which usually grew wheat or barley, but it was set by the hedge and so did not interfere with working farm machinery.

The Cooper family, in a further publicity shot for the Lucas Free-light, enjoy the novelty of television – even the blank screen is fascinating! My father constructed the brick fireplace in the inglenook for his sister. During the work, a bill for haberdashery from 1797 was discovered under the old mantlepiece.

The turbine had a tail fin to ensure that the blades turned into the wind. When access was required, a brake was applied to arrest the blades and the swinging tail fin. A built-in ladder could then be climbed, from which it was possible to emerge through a hole onto the platform; a vertigo-inducing step too far for the young explorer. Her Uncle Ted (my dad), however, in the “because it was there” spirit of the times, was soon to be seen, monkey like from scaling scaffolding on building sites, ascending the structure, camera strapped round neck, to make use of the photographic vantage point.

From the lofty height of the Lucas free-light pylon, a view of The Owletts, and its tree lined drive leading down to Lynn Lane, Shenstone. 1952.

By accident, in the background of a shot of my slender young mother practicing archery, the Free-light’s orchard pylon and control shed. 1952.

His camera came with him when he and my mother spent weekends at the farm. He recorded the atmosphere of a special era: the tidy functioning of a small mixed farm, symbiotically producing its own feed for its varied livestock, undergoing the advent of mechanised milking, and at the point that the hoofed strength of faithful Dolly was being superceded by tractor-power. And, inadvertently, he captured evidence of The Owletts’ short-lived foray into wind power, before The Grid……before any electric bills. Thank you, meticulous Mother, for writing the date on the back of the snaps: 1952.

Where The Grid has not penetrated, on Scottish isles and remote homesteads throughout the world, the Lucas Free-light still makes its green-energy contribution.

With thanks to Jo, and particularly to the detailed memories of Ros. Ref “Discovering Stonnall” by The Lynn & Stonnall Conservation & Historical Society, pub. 2012

Aunt Mary and Uncle Alfred at the Owletts, looking for all the world, like the figures in my Britain’s model farm – my favourite childhood toy.

That is another fantastic piece of work. It certainly was idyllic, but hard slog for parents, …they never stopped working, so there was a lot of independent time for me to go rooting about in the woods and fields. I don’t remember ever having seen the last photo with Pinto…lovely little pony.

A fascinating blog post giving us an insight into the not-so-distant past. (I was there!) Visiting Keeper’s Cottage with my Grandmother Florrie and Grandad Tom Hodgkinson.

Thanks, Jean. Glad you enjoyed it!

Hi Susan,

I have really enjoyed reading the posts on your website. I am researching family history and discovered the site along the way. I am pretty sure that Alf Cooper is my grandfather’s 2nd cousin and that Rosalind is 3rd cousin to my Mum (if I understand the cousins chart correctly). The mother of Charles Henry Cooper was the older sister of my GREAT GREAT GRANDMOTHER Jane.