Then Mom heard that a friend of a friend was looking for a “nice” couple to share her house in Broadway North with her. Landlords could be the choosers then. What would be the ideal tenants? A childless couple, both with good jobs, the wife neat, house-proud, and (according to Sister Magdalena’s letter of recommendation when she left school) refined and ladylike?

Mrs Hilda Lee found herself living alone at 81 Broadway after selling her late father’s grocery business in Walsall. The family had moved to the Midlands from the East Riding of Yorkshire. Mr Lee, whoever he was, had been a feckless type and the marriage had not lasted very long. To all intents and purposes Mrs Lee styled herself as a widow. She was an independent minded woman, and had enjoyed a good career at the Tax Office.

Number 81 was one of an impressive development of detached, faintly Tudorbethan family homes which had been built during the wars when the new “Broadway” had been cut through the previously rural community of Maw Green, forming a ring road on the east side of Walsall. Mrs Lee had called the house “Wallingfen” after her Yorkshire place of birth. My parent’s several years there, despite rationing and general austerity, have always sounded to have been very happy ones to me. The spacious house, of which they had sole use of one bedroom and one living room, boasted an upstairs bathroom, carpets, and a secluded rear garden. The cinema on Caldmore Green was a short stroll away for weekday evening entertainment, and at week-ends they could set off on their bicycles to enjoy picnics, fishing trips, archery, or visits to the family. Or on their tandem. Which my dad also used to get to work – with a comical empty rear saddle.

As a very poverty stricken new graduate, one of my homes was, incongruously in the hideously affluent Surrey stockbroker belt, where I shared a single room with my boyfriend, and, in turn, we shared the house with another four people: two builders who said they weren’t gay and a Dutch couple. “Weycroft”, near Byfleet, belonged to the Ambassador of Somewhere, who evidently didn’t need it, and it struck me as the sort of house that the protagonists of an Enid Blyton story would live in. The huge old fashioned kitchen was crying out for a bosomy “Cook” with a West Country burr who “did” for The Family, and there was a good acre of pergola and rock garden rich Home Counties garden. You could walk to a little lake, ruffled with water-lilies, where an abandoned punt swayed on a rope, begging questions about the fate of its last owner. The whole sepia tinted effect was ruined when a digger turned up entrench for new houses in the beautiful garden, only yards from the back door. Still – my modest share of the rent was fair exchange for the opportunity of living in a house like that for a while.

If you want a really good story about the window on another world afforded by renting a little bit of a big house, I am going to refer you to my cousin Ros – whose experiences on the subject were going to be a short aside within this piece, but, encompassing as they do a unique, evocative and occasionally hilarious description of a Staffordshire Stately Home – then in decline and now gone forever, have grown and grown into a real, live guest blog post!

I loved living in Crakemarsh Hall. I couldn’t believe my luck when I moved to Staffs Moorlands from the South of the County and found there was a flat vacant in this once wondrous Georgian Mansion. Okay, it was a bit basic. It was around 1966 so the bluey grey enamelled brute of a cooker on stout little legs was only about 30 years old, and the kitchen in which it stood was part of one of the many corridors. The draining board was wooden and a bit seedy, but there was room for a fridge and there was a bit of worktop.

I loved living in Crakemarsh Hall. I couldn’t believe my luck when I moved to Staffs Moorlands from the South of the County and found there was a flat vacant in this once wondrous Georgian Mansion. Okay, it was a bit basic. It was around 1966 so the bluey grey enamelled brute of a cooker on stout little legs was only about 30 years old, and the kitchen in which it stood was part of one of the many corridors. The draining board was wooden and a bit seedy, but there was room for a fridge and there was a bit of worktop.

When I got the key from Bagshaws and went with Mum to view I fell instantly in love. I have long had an interest in history, so the opportunity of being a tiny part of this once prosperous estate was not to be missed.

Turning off the Uttoxeter/Rocester road we passed a dainty little chocolate box gatehouse and drove a short distance beside iron park railings and past a grove of yew trees which lowered in front of the stable block, its clock stopped long since.

Tyres crunching we swung round to the side of the house, there was a tantalising glimpse of the front with its pillared portico, but we needed the side entrance, up several stone steps between rendered balustrades showing some of the bricks beneath the crumbling rendering. The sound of the opening door crashed cavernously in the echoing reaches of the servants entrance hall, our footsteps reverberated in the emptiness as we crossed to the next door, pausing to push the timer of the lights illuminating a stretch of corridor from the front of the house to the servants staircase, which was a nice little C18th example., but you had to be quick to get to the top before the frugal timer clicked and plunged you into gloom.

The next corridor from the top of the staircase ran back above the one just traversed to yet another staircase leading to another level. There was a little natural light from a window looking on to the rear courtyard of the house, and a light-well beside this second staircase which led even further up to the very top of the house, but we needed to turn off through a door to the right and back again in the same direction as the first corridor. We were wanting flat 2.

Flower Child. Rosalind, with companion. Her dress is Biba.

As we entered into the little kitchen, its further reaches were defined by yet another door, locked from “,my” side which led into yet another flat accessed from the rear courtyard up an outside wooden staircase. From the kitchen to the right was a door leading into a long low bathroom, a useful airing cupboard just behind, and housing a magnificent Throne at the far end next to the window, looking down onto the roof of my red Mini parked below, as did the wash hand basin in front of the window sill. Of course there was a monster bath on claw feet boxed in with hardboard. Part of my decorating scheme was to paint some “Love Baby” daisies on the cistern, gather some giant Reed Mace which I stuck in a big box of earth as a screen in front of the loo and some Art nouveauxey girls heads, full face, right and left profiles with tangling Medusa curls on the bath panel . When the Hall became derelict I was quite flattered to think someone had felt this panel was worth stealing.

On the opposite side to the bathroom two steps led down to a large bedroom with a capacious sitting room to the right. The windows to both were twelve feet high. They had wooden shutters which folded back into embrasures in the walls. They made THE most glorious clattering and rattling when they were closed and the iron bar dropped down to secure them. Who cared how much curtain material it was going to take !

I used to imagine what the sound had been like as the house was put to bed by servants clattering through every room, shuttering window after window to keep residents and contents secure for the night.

The house was an intriguing design of two three story ends linked by a two story range, and my flat was a cross section of this, with the bathroom overlooking the yew grove and stable block, and the bedroom and sitting room looking out onto the lawns and sprawling rhododendrons which sported the most massive blooms in their season. At the top of the lawn was a wood , and hidden within its shelter was a sunken ice house, only its domed roof obvious amongst the trees. The ice was taken from one of the lakes which was just beyond the rhododendrons in the park – now grazing land. This lake would have been beside the original main approach to the hall, still visible as a dry hard area amongst the grass in times of drought. An old illustration of a previous house indicated it was tree lined and was accessed beside the now demolished South Lodge, the twin of the remaining one which we had passed when we first entered.

At one point the lake was dredged and cleaned for the benefit of the angling club who rented it , and amongst the mud were hundreds of oyster shells. Yet another delicacy for the residents.

A walk through the grounds showed just what a variety of foodstuffs was produced on the estate. There was an utterly delightful Garden House with little pointy Gothic windows. One of the originals was still hiding in the warren of cellars beneath the hall. It was intricately leaded and I am sure the building it came from considerably pre dated the Hall in its present state… in fact another resident told me that when the present Georgian building was under construction, the family lived in the Garden House. The Hall had had several incarnations, there were Norman foundations in the cellars and the staircase in the front of the house was C17th – but more of that later……

Around the Garden House was a range of areas to keep the estate self-sufficient : a heated mushroom house; pineapple pits; peach, apricot and grape houses… and how I longed for one of those great greenhouses with the robust Victorian mechanisms for window opening. There were two gardens for vegetables and fruit, walled with warm red brick; and a tall water tower- a vital component. At night I sometimes heard a Nightingale singing in the abandoned gardens.

Along Hook Lane opposite the kitchen garden entrance was a “Halt” for the trains running into Uttoxeter, and when the family was up in London, the staff would take the fresh produce, especially grapes, up to the halt and despatch them to the capital for same-day consumption, and in times of glut – selling.

What a huge number of local people found employment there, apart from the army running the house, and the bevy of gardeners there would be estate carpenters, grooms , coachmen and manual labourers to lend a hand to anyone requiring a bit of muscle.

But it was all gone. Grass, rosebay and brambles suffocated the special houses, and fertile gardens , broken glass crunched underfoot in the greenhouses. The doors of the coach house where I had my garage were only just hanging on to their jambs, but I spotted in the stables the beautiful curved stalls with round wooden knobs on their finials and wondered what beautiful creatures had turned their gentle heads to look at the grooms bringing their fodder.

The stable yard was cobbled sloping gently to a central drain, all grassy and overgrown, with some slightly worn areas indicating which parts of the coach house contained somebody’s modern day carriage. Mine was a red Mini which had cost me £450 brand new..

Not everyone could have coped with living there I am sure…. coming home after dark and locking away the car, I had to teeter across the uneven cobbles without getting my stilletos stuck and then walk between the soaring dark yew trees to the steps leading into the hall where the light could be put on. The thrashing branches in a storm could be a little unnerving.

Many of the flats were empty when I lived there, some at the back condemned as unfit for accommodation, but JCBs Company Clerk and Chief Executive, lived in the first one on the ground floor : Basil Catford and his wife Nancy – Known as “B” and “Sammy” . Joe Bamford had actually used some of the stable block buildings for manufacturing trailers before the earth began to move for him.

Betty and Geoffrey engaged in the Herculean task of keeping the gardens at Crakemarsh tidy.

He had been educated at Stowe, his elder brother at Eton, and he worked hard at pretending to be vague and ditzy, but had been a highly qualified engineer, and played rugby for England, somewhere I have a picture of him in one of those glorious early racing cars whizzing round somewhere like Silverstone or Brands Hatch… and one of him on a London street in full fig with top hat looking like the Man Who Broke The Bank at Monte Carlo.

I did have a proposal of marriage from him but was regrettably unable to accept, as he was slightly older than my father, and by this time I was already caring for two nonogenarian parents and couldn’t cope with a third, despite being told that I would ” ….enter the Aristocracy under the Dukes of Devonshire and bear the name of Cavendish”….. ah me ! What might have been…..

For one week I had the incredible experience of being sole resident. B and Sammy were on holiday, as was Betty, and Geoffrey had gone up to London on one of his jaunts and I had free run !… I had the key to Betty’s flat to keep a check on things. Her bedroom and living room had enormous bay windows, and between them there was a soaring arched doorway leading into Geoffrey’s part which I was also looking after. I cannot tell you the joy of my first being able to walk through that archway and onto THAT STAIRCASE…. oh who had swept down there in their glorious gowns… from Civil War to Flappers and slinky bias cut art deco vamps ……

It was a great broad descent from the galleried area in front of the archway. The whole thing was a riot of carving, each newel post boasting an overflowing basket of fruit and flowers, acanthus leaves swirling between each post. The first descent was towards the window on the front of the house above the portico, then a turn down to the right and a small area housing a weighty console table with a marble top and a fat gilt cherub clambering through golden overhanging foliage , and then another right turn down into the entrance hall which it dominated.

To continue straight ahead from the bottom step took you along to Geoffrey’s sitting room to the left and opposite the former ballroom. This now housed an antique bed of enormous proportions where visiting daughters occasionally roosted. Both rooms were entered by flinging wide ten-foot high double mahogany doors. What a way to enter a room…

The fireplace in Geoffrey’s sitting room was white marble with a carved portrayal of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, Daniel looking slightly chipped about the arms as if the lions had decided on a little snack. Either side of the doors was a pair of Regency bookcases recessed into the walls , They looked like rosewood with gilt trims , and some inlay. Sadly, they were some of the first things to go as Geoffrey ran out of funds. There was a black C17th display cabinet on stand which I admired enormously.

The entrance Hall was impressive in a restrained way. Entering from the portico there was a pair of half glazed double doors, the bottom of the staircase was to the left and to the right sturdy pillars supporting the first descent of the staircase. It was the exact twin of Sudbury Hall staircase, though Geoffrey swore it was by Grinling Gibbons. Opposite the exterior doors was a hefty oval gilded mirror reflecting the light from the glazed panels, and indeed the identity of anyone who happened to be entering… maybe it was to give staircase-descenders the chance to bolt back upstairs if it was an unwelcome visitor. The area behind the pillars formed a small room and it was here where Geoffrey kept his porcelain , he was a noted authority on ceramics in The Potteries, particularly Longton Hall of which he had the best collection in existence… but that all went the way of the bookcases.

In typical country house style walls were smothered with paintings and prints.. pictures of every description, until hardly an inch of vacant wall remained. On the side of the staircase wall was a copy of the triple portrait of King Charles I, from full face right side and left, and some priceless Moghul Indian miniatures given to an ancestor after service on the sub-continent.

The most intriguing picture carried a curse. It was of a Victorian Worthy standing before a balustrade, I think it was of Richard Cavendish who had been the first of the Cavendish family to live there and he had so loved the place that he insisted that this portrait should hang there ” whilst a wall of Crakemarsh stood…” – and it did , until the staircase was taken out by the Bamford family along with the mahogany doors “for preservation”.

Even then it still hung there, with bare bricks marking the former position of the staircase and facing the gaping doorway to the crumbling ballroom. Until of course the obligatory Toe-Rag cut it out of its frame and rolled it up under his jacket and sold it for a fraction of its worth. I wonder if the curse did befall him?. I do hope so.

Betty Old and I actually thought for a fleeting moment that there was something in the curse when the Hall was on the market and Mr Stott came to view and asked us ” Why is that gruesome portrait left hanging in the entrance hall?”… I think my hackles and Betty’s rose at exactly the same moment. We asked falteringly ” Why… gruesome?”, ” There is blood dripping from the hand.” The most significant of looks passed between us before she explained the legend, but he wasn’t in his car before we were skittering down the staircase to check, hearts in mouths, but it was only shading on the underside of the hand caught in the light from the windows of the doorless ballroom. Phew!

If a fine summer’ s day happened to coincide with a day off work, attired in my bikini, I would unlock the door at the end of my kitchen and walk through to the far end of the empty wing and climb up to the top room where small windows opened directly onto the leads. I would climb through and stretch out on a towel , utterly hidden from the world behind the parapet which surrounded the roof.

The view was stupendous, all across the parkland and woods over the ha-ha and down to the meandering River Dove and towards Uttoxeter…. pronounced variously Yew-toxeter; Utt(as in utter)oxeter; Geoffrey said something like Axe-eter and locals pronounced it Ootcheter which was probably the most ancient.

There were various hefty ancient specimen trees dotted around and two lakes, but only one could be seen from my sun-bathing spot, the other being on the Rocester side. On the roof slates were scratched names and initials of workmen who had been proud of either building or re-roofing. Nobody had been up there for decades and I well remember an extremely startled jackdaw, of which there were tribes, sailing a thermal and aiming to land on the parapet, only to find a sprawled human in his territory. He quite distinctly said “ERK!!!” as he dropped off the edge as the quickest mode of escape. I did laugh but felt very guilty for having invaded his home.

In the scheme of things it wasn’t an overly grand house, with only about 38 rooms I think. It was Grade II listed and I do not know to this day how it had got into the sad state it was in, although far grander Markeaton Hall in Derby,where Geoffrey had spent his childhood under the watchful eye of the fearsome Mrs. Munday, had already been demolished. There was a giant stone urn from the parapet , about five feet high, standing in the flower border as a keepsake from his former home.

Mr Stott bought the house and I asked if I could rent the front part after Geoffrey left, but was refused and it was left empty and disintegrating.

Across the road from the kitchen gardens was the Home Farm to the Hall, and I subsequently married Henry, the son of the Prince family living there. It wasn’t far to move my furniture and what I could carry over, I did.. Whilst struggling to carry my long case clock – works removed and already at Home Farm,- I must have cut a comical figure with my arms around its body and my feet tottering beneath. I met B coming back from garaging his car after work and he rendered me helpless by quipping as he passed ” I don’t know why you can’t wear a watch like everybody else.”

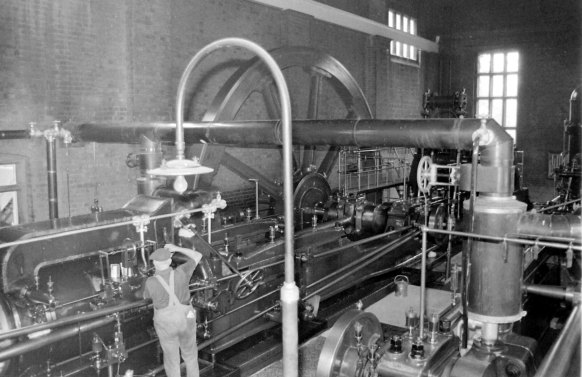

But I was used to hauling and mauling. If I wanted a fire I had to carry my copper coal helmet down all the corridors and stairs and outside, through the yew grove and into the area at the back of the Hall which housed the Offices – laundry, bakehouse, brewery etc, and one range was the resident’s coal holes. By the time I had lugged it back up the stairs I was too warm to need a fire for a while. I used to think of those who had gone before me up and down all day keeping fires going throughout the house, a great cooking fire in the kitchen, the meat jack mechanism still hung in the chimney, roaring fires in the living rooms, smaller ones in the bedrooms. No wonder they had to employ so many people.

Eventually it was re-sold and bought by JCBs and the staircase and mahogany features removed, so was then little more than a shell, and when the lead was stolen from the roof , it of course began to let in water, so very sad .

The house was no stranger to sadness, old buildings all have witnessed their share, Betty had told me about the lady who had lived in the flat beyond mine who had lost her husband and would constantly cry out ” Why have you left me ?” accompanied by the mournful howls of her dog.

Geoffrey’s father had been drowned when the Titanic sank, his mother and her maid were rescued in one of the lifeboats. She was a New Yorker, daughter of the Siegel Stores Empire and spent the years she lived as a widow at Crakemarsh removing the white paint from the staircase, I know not at what point it had been so decorated, but it was her life’s work to clean it off. She died a very few years before I got there… I was THAT close to being able to speak to someone who had been on The Titanic… though I expect there was an aura around her head which gave off the message ” Do NOT mention The Titanic”

The saddest thing which happened to me was after I was living at Home Farm, and Chrissie, one of my cats, had been missing for five days, as a last resort I went into the Hall shouting her name….. and was answered by the most relieved little cries… ” I’m here !… I’m here ….” but the cries seemed to come from all over the house, inside and outside, and Henry and I could only assume she was in the labyrinthine flue system and her voice was coming down all the empty fireplaces in the house. She was desperate and cried and cried. Henry even made a hole in the horizontal flue in the kitchen and put cat food there, but to no avail.

The following day I went and called again, but was met only by a thick silence. She must have died of fear, despair and dehydration.

Eventually one wet and windy night with no electricity supply in the Hall a fire broke out in the entrance hall, spotted by Johnny Walker the author of ” History of Crakemarsh” who was living in the Garden House and as a baker, was up in the small hours to get started early. The fire was put out and Henry later saw some partially charred straw bales had dropped down into the cellars.

Now beyond saving, the Hall was demolished and new houses built on the site, I wondered if as the demolition team went about their work if anyone spotted the mummified body of my little Chrissie.

It’s a hauntingly sad note to end on Ros – but I treasure the whole story. A very readable and comprehensive History of Crakemarsh by Johnny Walker tells the whole story of the settlement and can be found here: http://www.search.staffspasttrack.org.uk/content/files/55/177/886.pdf