Here’s an intriguing but flimsy scrap of Horton family legend blowing about in memories of conversations with my dad – that, at his boyhood home in the rural hamlet of Footherley, he’d watched Hull’s own famous aviatrix Amy Johnson landing her ‘plane.

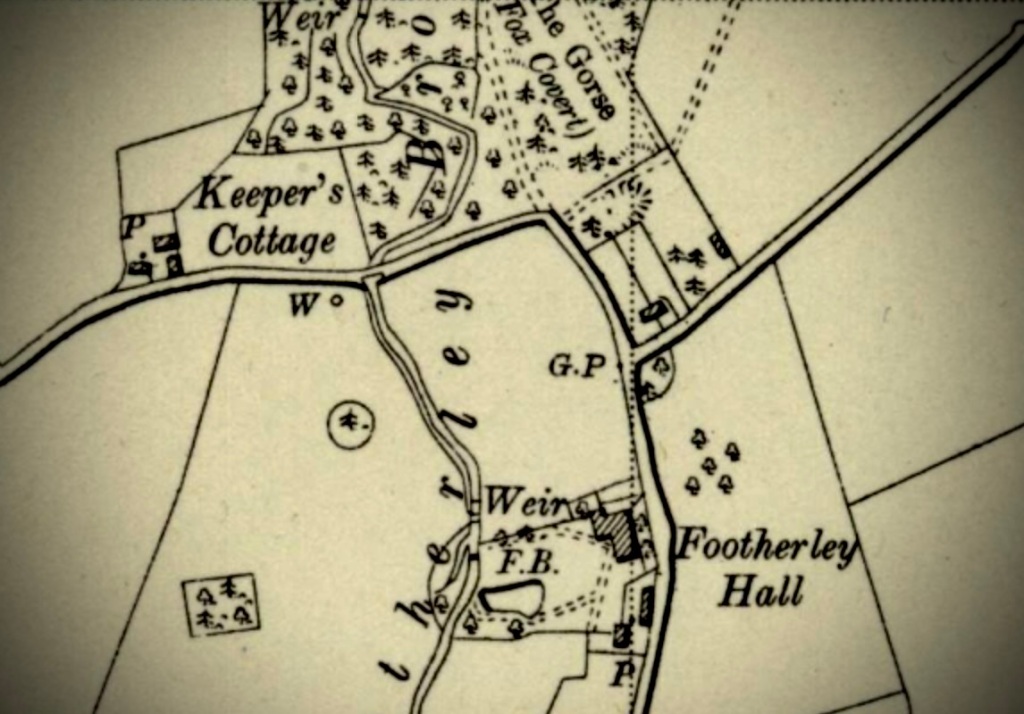

Is it a clear bright 1930s morning, as two boys look up with astonishment to see a little aircraft descending from the sky? A Saturday? Because my dad, Ted, and his next oldest brother, George, are not, it seems, in reluctant attendance at Shenstone school. Are they outdoors, busy in the garden plots surrounding their home, the old Keeper’s Cottage, or out with Pop in its feggy field that runs down to the brook and the woods?

Perhaps they are absorbed, fastidiously tending a shotgun, employing eyeleted rod, and oily rags, as freshly persecuted pigeons, strung together by their spindly leather ankles, hang, soft and grey, outside the cottage door. In coming years, that old black hook may bear a gaudy pheasant cape or two, when Uncle George becomes apprenticed to the poacher’s craft.

Or can I hear the boys scampering out from the cottage’s small, dark and dusty interior in sudden curiosity as the comb-and-paper purr of a Puss Moth is first heard, only to witness it disappear from sight just over the the high banked hedge on the opposite side of the gritty lane and bounce to a halt just over the Footherley Brook? This field comprises part of the 29 acres of the estate of Footherley Hall.

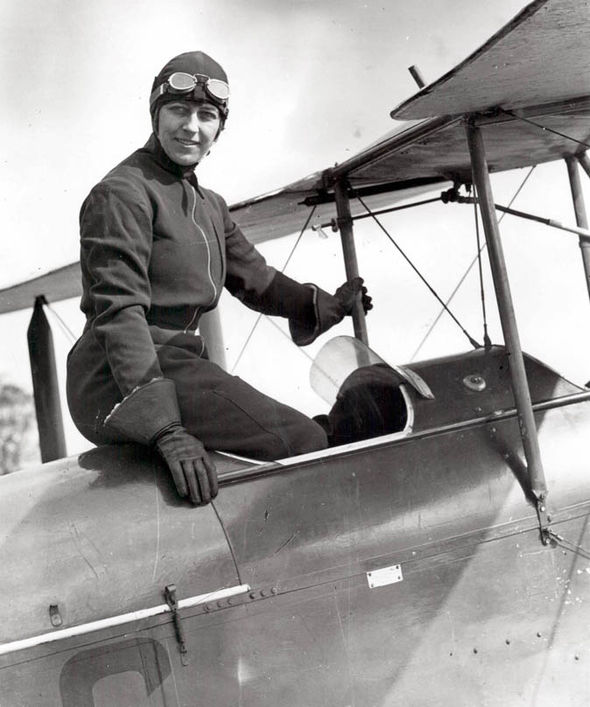

Rushing across the lane to peep through the hedge, the boys watch, astounded, as Amy Johnson, like a butterfly from its chrysalis, extricates herself smoothly from the cockpit with a practiced movement, and strides, the straps of her flying helmet loosened, to the grandly porticoed door of Footherley Hall, the Ellison Family home.

The Footherley Hall of the 1930’s presents itself as it was remodelled in Georgian times as a modestly grand brick mansion. Records depict its former incarnation as a Tudor farmhouse, passing, as it did, through the hands of the intermingled dynasties of old Shenstone gentry; the Sylvesters, the Browns, and the Floyers. But its history is more venerable. It stands sentry beside a section of Roman roadway. This now dainty, grass-hemmed lane was once Ryknield Street, a thoroughfare that echoed to the sudden footfall of the XIV Gemina and XX Valeria Victrix.

Alfred Ellison owes his fine home and enviable lifestyle to his venturesome father.

George Ellison Senior was born near Manchester in 1874. Following attendance at Manchester Grammar School, he completed his education at Winterthur University, where he met his Swiss wife, Hermoine. George, just 20 years old, then gained employment with the pioneering Westinghouse and Western Electric Company in Pennsylvania. The couple were married in America in 1894, where the eldest of their five children, Alfred, was born. In 1898 the now growing family decamped to Paris, where George was involved in the making and selling of electrical switchgear on his own account. And so to the English Midlands, the obvious choice for an engineering company to recruit the skilled labour they required. He founded his Birmingham firm in 1906. His innovation of the flexible, versatile, electrical insulation material he invented and named “Tufnol” is so outstandingly successful that the brand will live on into the 21st century.

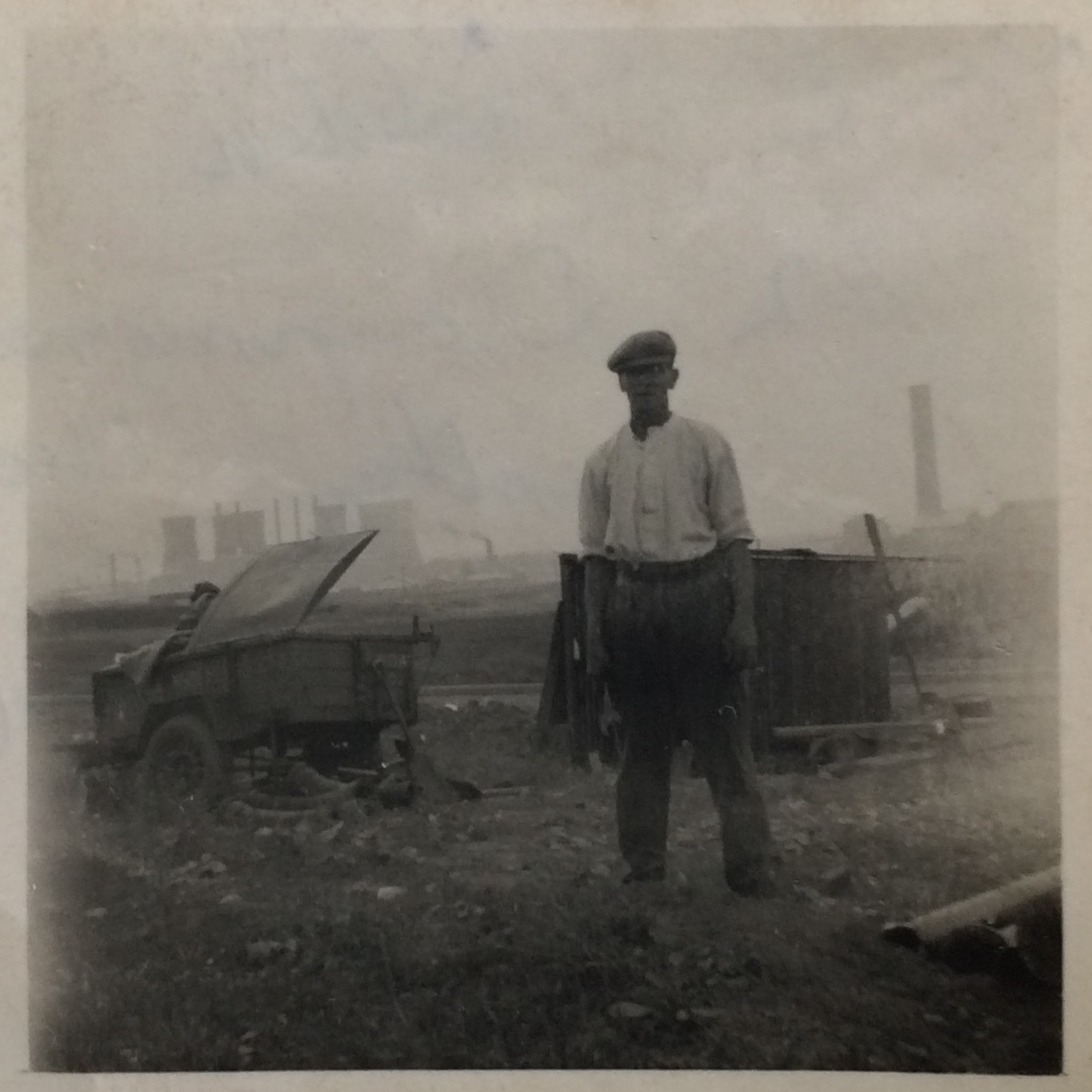

A commemorative painting of activity at the Perry Barr works of Ellisons, commissioned by them to commemorate the end of the Second World War. During the war, the Ministry of Aircraft Production took over their enterprise.

Alfred Ellison is not unique in having undertaken the migration north from the industrial conurbation where his family money is made, to pleasant, rural, Shenstone……. A stone’s throw from his own Aston works and the Ellison companies at Perry Barr are the Aston wire manufacturies of the Godriches, who are to take up residence at nearby Shenstone House in 1940.

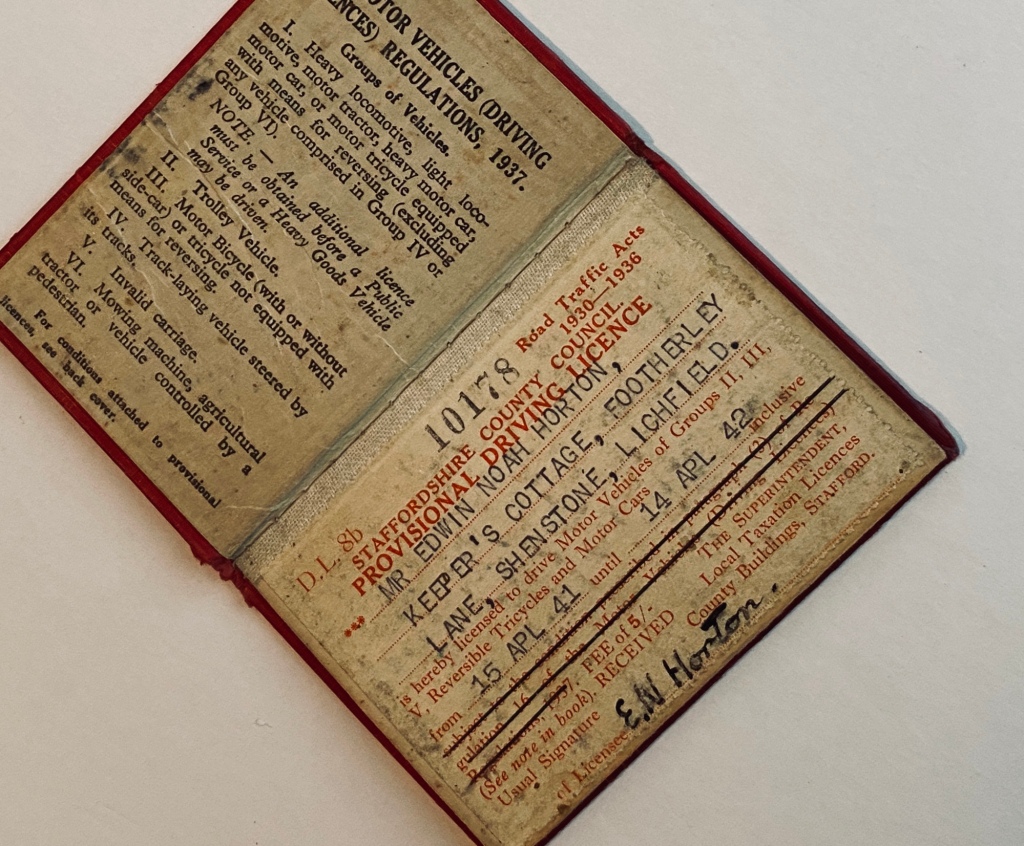

As war begins to take any adult men away, servants, already a dying breed will be in shorter supply. My dad, by then a big, strong, capable lad, will obtain a driving licence at the tender age of 15, to take up stop-gap employment with Godriches as their “chauffeur gardener” (as he will proudly describe it to me decades later). His duties will involve ferrying their daughter – a girl barely younger than he is – to and from private school, in a vehicle the likes of which his family never dreamed of owning. As the only male servant in the household, he will be responsible for carrying fuel upstairs for the bedroom fireplaces. assisting the maids, recollections of whom, in their fetching lace aprons, will linger long.

Indoor staff can be a little more easily recruited and afforded in these pre-war years:

A maid opens the the door of Footherley Hall to Miss Johnson and invites her to freshen up in one of the hall’s three bathrooms, before taking tea in one of its three charming reception rooms. Recent sales particulars of the property have also romantically described an “old world garden with trout stream; undulating, well timbered lawns; grass walks with herbaceous borders.”

Additionally, Footherley Hall boasts two garages and stabling, where, in the Ellison’s time, a fine parade of the family’s leisure and sporting cars are housed. I suspect that Amy is as eager to peruse the vehicle collection of her host, Alfred Ellison as he is to show them to her – She is drawn to all engine propelled sport. Late in the ‘30’s she will compete in the Monte Carlo rally in a 4.5 litre Bentley.

Was there ever a particular car that you regretted selling? My father often reminisced with pride about his Ford V8 Pilot, an impressively large and powerful vehicle for its time, but a thirsty liability when fuel prices rose dramatically in 1956 in response to the Suez crisis. Its stylised, aircraft-shaped, pure art-deco hood mascot is travelling through life with me still.

For Alfred Ellison, let us assume that of the many impressive racing cars that have passed through his hands, it is the “Veille Charles III” that lives most vividly in his memory. A Lorraine Dietrich whose amazing pedigree, and his adventures with it, must provide an ample source of anecdotes to entertain Amy with.

Alfred Ellison, with his brother, George Ellison Junior, in the 1912 Lorraine Dietrich the “Vielle Charles III” in the paddock at Brooklands, having driven it from Footherley to Surrey.

It was raced in France before being brought to England by Sir Malcolm Campbell in 1920. Alfred Ellison had acquired it by 1923, and drove it in 20 races at Brooklands before selling it in the late 20’s.

But Amy and Alfred, this pair of pre-war petrolheads had more yet in common and very good reason to seek each other out.

Alfred Ellison first flew an aircraft as a young man during the First Word War, on active service as part of the Royal Flying Corps. He extended his flying experience in following years by attending air rallies as part of the Midland Aero club in various European capitals, but it was when, in September 1934 he and his brother, George set off for South Africa in his own DH Puss Moth to visit potential customers that the story of “The Flying Business Man,” really set the local press alight. They even made an unsuccessful attempt on the record for the fastest journey on the return journey from Cape Town.

The record stood at 7 days, 7 hours and 5 minutes – to the credit of Mrs Amy Mollison, (AKA Miss Amy Johnson) flying her DH Puss Moth “Desert Cloud”. That is – flying solo.

As Mr Ellison, leaving the hall in one of his fancy cars, rounds the ninety degree corner of Footherley Lane, bumps over the Footherley Bridge and passes “Keepers”, the Horton children might wave to their neighbour from their remote cottage world, in which there is no indoor plumbing, electrical supply, or any matching crockery.

Years later, after Ma (my Granny) had died, I remember finding Grandad – who was a charming conversationalist and never without a flirtatious twinkle in his one real eye – holding court in the tiny living room of the cottage to a glamorous laughing Freda, (Mrs Phiip Mist) Alfred’s daughter.

Oh, my Uncle George.

I can feel his attitude of roguish indignation in his response to a summons for trespassing.

The Lichfield Mercury of July 30th, 1937 reports:

“George Horton of Keeper’s Cottage, Footherley, a farm labourer [he was 15 at the time] was summoned for trespassing on land in the occupation of Mr Alfred Ellison at Footherley. Mr C L Hodgkinson appeared for Horton, against whom it was stated that he was seen on the land….two shots were heard and the defendant was seen with a double barrelled shotgun and two spent cartridges at his feet. Horton told the magistrate that he was on his way to Towers Farm when stopped. he had an unloaded gun with him, but had fired no shots, although he had heard shots being fired. He went into the plantation to send some ducks belonging to his mother back up the brook. He had his gun with him because he was going clay-pigeon shooting. The case was dismissed.”

References:

“The cars of Alfred Ellison” and “The Flying Ellisons” – articles for Motorsport magazine by Bill Boddy.

Birmingham History Forum.

Trusty “Find my Past”

The will to find time to do this at all:

Allan Tranter’s belief in me.

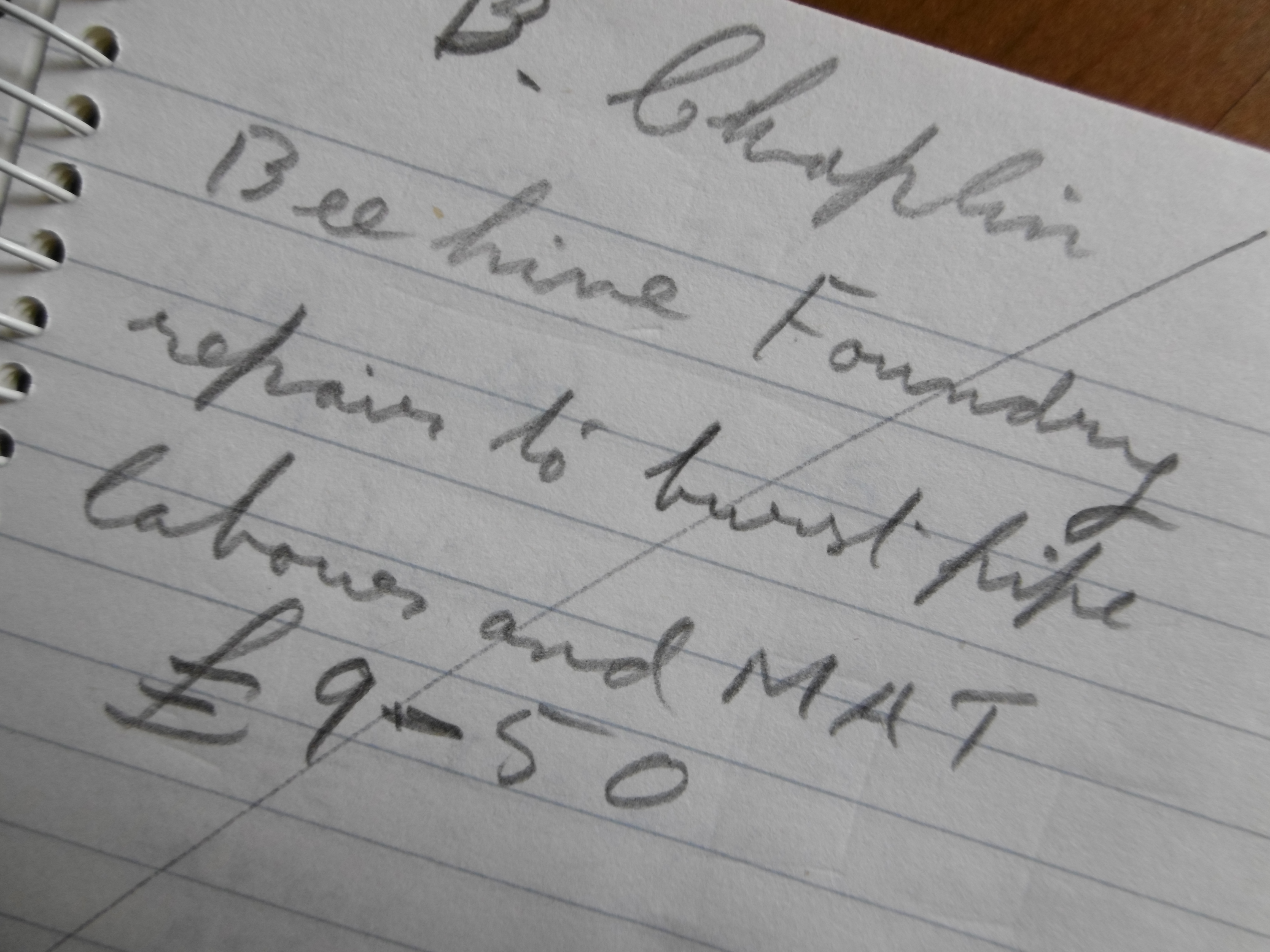

It wasn’t all about the mortar and the paint. The customers were his friends. He didn’t get rich out of them, that’s for sure. Interesting tales filtered home of lives beyond our experience. In Four Oaks, Miss Harvey’s ancient aunt, who lived with her, had been a suffragette, and armed with an enormous ear trumpet, was able to detect my father’s responses to her fiery anecdotes of activism before the first war. In Brownhills, Barry Chaplin has sunk all of his money into the “Beehive” – an old pub, converted into a foundry, and intended to make a fortune. My dad pointed the brickwork under the upper windows by leaning out of them with me holding on to his ankles. This is true.

It wasn’t all about the mortar and the paint. The customers were his friends. He didn’t get rich out of them, that’s for sure. Interesting tales filtered home of lives beyond our experience. In Four Oaks, Miss Harvey’s ancient aunt, who lived with her, had been a suffragette, and armed with an enormous ear trumpet, was able to detect my father’s responses to her fiery anecdotes of activism before the first war. In Brownhills, Barry Chaplin has sunk all of his money into the “Beehive” – an old pub, converted into a foundry, and intended to make a fortune. My dad pointed the brickwork under the upper windows by leaning out of them with me holding on to his ankles. This is true.